As founder and CEO of Cruzeiro do Sul Educacional, one of Brazil’s most influential and successful private education institutions, highly regarded professor Hermes Ferreira Figueiredo has been in the field of education for half a century. A lifetime in the sector has brought with it a unique take on the changes that the Brazilian system has undergone, specifically the privatisation of higher education and the recent boom in such privately funded universities. He spoke to The Report Company about the challenge of attracting an increasing number of international students whilst consistently improving the quality of the graduates they produce.

The Report Company: How would you appraise Brazil’s education sector?

Hermes Ferreira Figueiredo: I agree that our numbers are below those of our neighbours and of Europe. I also believe we have to recognise that there has been a significant improvement in the sector, both in quality and quantity. When policies dedicated to including more students are implemented, there is often a price to pay in regards to quality, but despite the greater influx of students into higher education, quality has also improved.

When the previous minister of education set the goal of having children know how to read and write by the age of eight, he was recognising that we were lagging behind. I'm not just being nostalgic, but I'm 76 years old and when I was seven, I already knew how to read and write and some maths, but fewer kids were formally educated back then. Today, more students are being taught, but public policies have changed. Day cares and pre-schools were always under the responsibility of municipalities, but it was an area that was often overlooked and the state had to step in as a result.

TRC: Education is now private rather than public-funded. Is there any reason to question that situation, when there is an argument that profit may be put ahead of education, or is this an outdated idea?

HFF: This dichotomy between public and private education started with Jesuit priests because Anchieta was the first teacher in Brazil, and he was in the private sector. With every constitutional reform Brazil goes through, the discussion arises again, but I believe the sectors are equally important and one complements the other.

The goal of both is the educational and cultural elevation of the young, of the population as a whole. We are only tools. If the private sector is capable, let's use it. Students won’t care; what matters is that they will have benefited from public policies that put them in a position to exercise their full citizenship. But I believe this discussion will be endless.

“Quality is our first concern. Ninety percent of our professors have masters or doctors degrees, we have three PhD programmes and nine masters degree programmes, more than the two and four required by law.”Tweet This

TRC: Is the wave of mergers and acquisitions that has followed the change in the law a positive move?

HFF: This consolidation started in 2007 when Anhanguera started buying all sorts of institutions, big and small, to increase their reach and their presence. Estacio followed suit, then Kroton. Seeing their financial successes, international groups became interested in us and what we had created.

I am part of the 1970 generation which revolutionised education in Brazil and after which all these large private groups emerged: Uniban, Unisid, Sao Judas Tadeu, Uninove, Unimar, Potiguar, Universo, Estácio. The 1968 university reform made it easier to start new courses, because if the same strict legislation had been maintained, we would have only three to four percent of 18- to 24-year-olds in higher education. The government realised that the country would be in a terrible situation if it did not move towards the private sector so in 1968 the law was changed and in 1969 and 1970, the movement to create new private courses started. In the 1990s, the LDB [Bases and Guidelines Law] added further flexibility, making it possible for entire universities to be created.

The movement toward consolidation opened our eyes. I said to the people at SEMESP that we were educational entrepreneurs, that we had always expanded into education, and that we needed to continue to do so as businessmen to protect ourselves. Educational institutions usually use their own financial systems, but we had been working with several banks for a long time, and they told us that we had credit available, that we should spend it and grow.

TRC: What is your strategy and what are your values?

HFF: We are not desperately looking for acquisitions. Our strategy is multi-brand; to maintain the values of each institution because these are not financial institutions, they have roots in their surroundings, their own cultures and history. Our marketing is brand-specific so that the universities continue with their values, culture and history, I want them to feel like they own themselves.

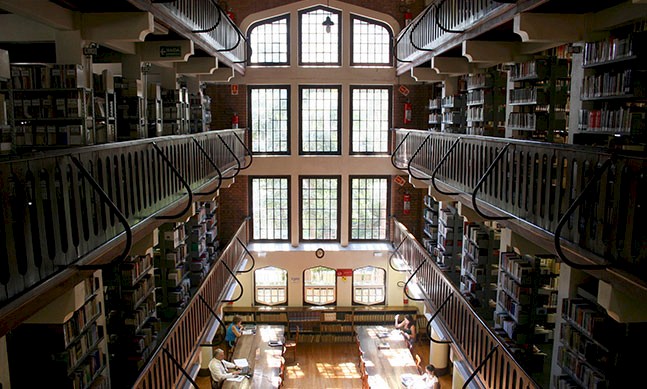

Quality is our first concern. Ninety percent of our professors have masters or doctors degrees, we have three PhD programmes and nine masters degree programmes, more than the two and four required by law. We are the private group with the largest number of stricto sensu courses and we were one of the first private institutions in the country to get funds from Capes, CNPq and Fapesp for research. It is in our DNA not to quit on masters and doctors degree programs, because this, in turn, increases the quality of undergraduate courses.

TRC: What do you think the perception of Cruzeiro do Sul is today?

HFF: It is very hard to evaluate yourself, but we know that both the regulatory agencies and our competition think we have high standards. Since 1990 we have run a project dedicated to institutional evaluation of the work environment, student satisfaction, teacher satisfaction and so on, even before we set up the Permanent Evaluation Commission (CPA). It is an independent department composed of employees, professors and members of the community, all of whom are surveyed to create a full picture.

We try to maintain an environment in which people like to work and we have seen that in practice. I think we fulfilled our role of creating a pleasant working environment. We do not censor any ideology either and people can be comfortable and confident being liberal, socialist, communist, atheist, evangelical, Catholic or Jew, but they have to be pluralist; they are not here to preach.

“We want to internationalise, but we want to be a centre of attraction, too. I tell my deans that we have to stop looking to Coimbra and Harvard and so on; we should be looking at the Americas.”Tweet This

TRC: How do you see the evolution of internationalisation?

HFF: For us, it is more difficult to send students abroad than professors. Given that around 70 percent of our students study at night because they work during the day, financial factors are considerable, as is family. But we have many students on the Science without Borders programme. I went to its inauguration in Washington, but I have my reservations about it, too. England or France or the United States are not so interested in internationalisation; they want paying students and their main interests are economic, but we also need their students to come to us.

We have received students from Japan, from Portuguese-speaking countries in Africa, people from Mexico. Students from England, Spain and Venezuela come for our graduate courses in odontology because it is so highly advanced, so yes, we do want to internationalise, but we want to be a centre of attraction, too. I tell my deans that we have to stop looking to Coimbra and Harvard and so on; we should be looking at the Americas. The quality in Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador, for instance, isn’t as high as it is here, but we have been ignoring them as clients. We should be doing the opposite.

TRC: UK finance minister George Osbourne came to Brazil recently to launch the Newton Fund with Confap, recognising the successes of the country's scientific community and seeking stronger ties between the two nations. What future do you see in such links?

HFF: We see every form of exchange as positive. I carried out an exchange program in 1997 with Cuba and made an agreement with the University of Havana, whose professors had been trained in Eastern Europe, and none of them went back to Cuba. They have been here ever since and are excellent professionals.

When I was a professor we were not evaluated and no one was as committed to their jobs, teaching just two classes a week. These professors came in and changed that mentality. They arrive early in the morning and leave late at night because it's what they like doing. They enjoy the lab life, having discussions with students, and this attitude became infectious. It wasn’t that their ‘job’ was being a professor, they simply ‘were’ professors.

Sometimes, people say that there is a shortage of trained professionals in Brazil and that the quality of the private sector is not good enough. How can the seventh largest economy in the world be driven without trained professionals? We have many. Moreover, around 93 percent of management professionals in the 500 largest companies in Brazil come from the private sector, and around 87 percent of directors, 75 percent of the presidents. Where would they have gone if the private sector was not here? If we were to depend solely on the public sector, we would be bankrupt.

“Sometimes, people say that there is a shortage of trained professionals in Brazil and that the quality of the private sector is not good enough. How can the seventh largest economy in the world be driven without trained professionals?”Tweet This