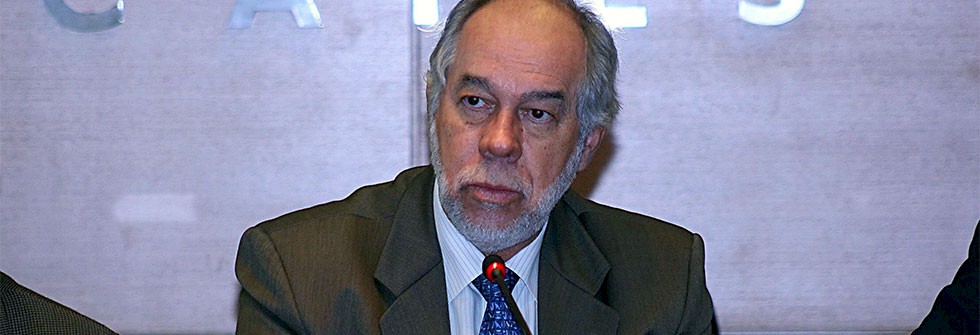

As a key arm of the ministry of education, Brazil’s CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel) has played an important role in the growth and consolidation of higher education in the country since 1951. Professor Jorge Guimaraes took over the presidency of CAPES in 2004, and has been instrumental in the rapid, ongoing expansion of Brazilian higher education over the last decade. The Report Company met with him to find out more.

The Report Company: What is your take on the recent expansion of the higher education system in Brazil?

Jorge Guimaraes: Brazil’s higher education system is still in its infancy. CAPES was founded in 1951, when Brazil had five universities. We had independent schools, but the oldest university we have was created in 1934, when Harvard was already 300 years old and some universities in Europe at least twice that. Brazil was a Portuguese colony for more than 300 years, during which no such institutes were created. Even though our neighbours Argentina, Mexico and Colombia have centuries-old universities, Brazil failed to follow that path.

The fact is that CNPq (the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) and CAPES were created in 1951, and practically 90 percent of all universities in Brazil are younger than both of them. That does mean, however, that there isn’t anything like CAPES anywhere else in the world. There are accreditation agencies, but they don’t play the role of a development agency like CAPES does. We have been evaluating graduate courses since 1974 - even the British system was only implemented in the 1990s. At the time, I was the director of CNPq, and I was invited to the second round of discussions of the British system, which started almost 20 years after CAPES.

Shortly after World War Two, the Brazilian authorities realised that the country needed to be part of the world in the best possible aspects: education, science and technology. Our universities are autonomous, but we evaluate all of them and no institution can create a graduate course without going through CAPES. That was important because, since the development stimulus system is very strong (we offer several thousand fellowships and grants, support for students abroad, a web portal on scientific journals and periodicals), even the private system accepted our system.

Our undergraduate courses are still deficient, but our graduate courses are at an international level. The other important element we already have is access to the literature, through our periodicals portal, which includes the full text of all periodicals in the world offered for free for our students. If students go to a class on dengue fever, they can then follow it up online and access the latest review on the disease by, say, the London Institute of Tropical Diseases.

TRC: What opportunities do you see for global partnerships in education?

JG: The process of internationalisation was amplified by the Science without Borders programme, but CAPES had agreements with more than 40 institutions even before that began. What it did do was strengthen and institutionalise that process, which previously had been done on a very individual basis. After the programme started, we met with a lot of pessimism from American universities, but that only lasted until we sent the first 1,500 students abroad. Today, universities are lining up to receive our students and we are signing a lot of agreements there. It is the same with Europe.

We are not just signing with overseas ministries of education, however, but also directly with universities. Brazil started late, so it has to walk quickly and take shortcuts. International cooperation is one of those shortcuts and our collaboration with top institutions throughout the world has been a powerful tool. We have a recent and important partnership with the University of Nottingham, for example, which has one of the best schools of pharmacy in Europe. We signed a partnership with three of our schools of pharmacy and a knowledge exchange is already underway, so we are able to use their experience. Another agreement was signed with the University of Nottingham for support joint research projects in the field of drug discovery. Seven projects of different Brazilian institutions were approved and are under way.

All of this is part of a more general effort to internationalise our universities. Although many of us have studied abroad, our level of internationalisation is relatively low due to a lack of joint cooperation agreements like those that exist between England and France or Germany, or the US and France. Our neighbours Chile and Argentina have more of that sort of cooperation than we do, so internationalisation will help with that process too.

“The process of internationalisation was amplified by the Science without Borders programme, but CAPES had agreements with more than 40 institutions even before that began.”Tweet This

TRC: Now that the next stage of the Science without Borders programme is underway, what is being done to improve its execution?

JG: World-class universities are small compared with ours. They are very focused on basic and applied research; they are fully autonomous and accountable. None of these elements are particularly strong here yet. They may be autonomous, but they are not very daring, and the government and regulatory agencies interfere a lot.

There is much more to internationalisation, however. There is the need for international syllabuses, courses in English and other languages, living on-campus, the need to speak a second language, being around students from all over the world. The students in the Science without Borders programme are being exposed to that and are bringing it back to the country. Less theory, more practice, and much more besides, including scientific cooperation.

The model we used was important to kick start the programme, and although there were some complaints that the universities didn’t get as involved as they could have done, which I would agree with, this was a good start. The problem is that some universities have more than 200 agreements for student exchanges, but don’t have the resources for them and the students’ families end up paying. Science without Borders came to solve that problem, and it has been a success. It is a programme for students, but the universities have to work with them and stimulate their interest in going abroad.

To truly internationalise, just sending students abroad isn’t enough. We have to bring others in as well. Bringing students in is the responsibility of the universities; CAPES can only help. They will be able to participate much more than in the beginning and discuss syllabuses with their partners. However, since our universities are very big and lack some key ingredients, another strategy for internationalisation is supporting them in what they do best. CAPES has been evaluating graduate courses for 40 years now, so we know which are the best departments in each area. This will be our sectorial approach to internationalisation. A little more than forty of our universities have courses that scored six or seven on our scale that goes from one to seven, where six and seven are international-level scores. Courses that score one or two have to be closed, no matter how good the university is. This is what the accreditation agencies that other countries have cannot do, because we can use our financing as coercion.

The University of Sao Paulo, for instance, is one of the best in Latin America, but it will have to be internationalised in sectors, not as a whole. This was the university that sent the most students abroad through the programme. It knows where these students went and it has 90 graduate courses with a score of six or seven out of more than 200 courses.

TRC: Do you think universities will have to restructure in order to internationalise?

JG: We have listed the best courses in all the universities and carried out a study on the experience of the Science without Borders programme. We are going to heavily finance this so-called sectorial internationalisation so that the country’s best graduate course in maths will receive special assistance. There will be an invitation for bids, which means that every university will do their own planning for those specific courses.

We asked these courses what they think they need, and what we need to do, for them to become more international, and they responded that things like more flexibility, attracting foreign professors and the easier purchase of equipment would help. We are still evaluating, but the main issue seems to be the lack of technical personnel and support. They want more mobility, so rather than ask CAPES every time they need to go to a congress in London, they will get the resources for that. This is, in our opinion, the quickest, easiest and most efficient way to address internationalisation. This way, it’s not only about individuals; you have the full commitment of departments, professors and students.

“Brazil started late, so it has to walk quickly and take shortcuts. International cooperation is one of those shortcuts and our collaboration with top institutions throughout the world has been a powerful tool.”Tweet This

TRC: How do you see the future of the relationship between Brazilian universities and the private sector?

JG: This issue is more important for some universities than others, and we started very late, so the integration between universities and companies is still growing. There are few examples in which particular universities have leaped ahead, though: PUC-RS has the best technology park in Brazil; PUC-Rio also interacts closely with companies and Coppe-UFRJ has a great partnership with Petrobras. In Brazil, around 50 percent of the money invested in R&D comes from companies, but the vast majority of that is from Petrobras. The majority still do not have that culture. The private sector used to complain that our academia was not very willing to cooperate with them, and although this was the case in my generation, it is not so anymore.

TRC: With the economy struggling, what is the best way to stimulate investment in R&D from the private sector?

JG: The government has been making big steps, but there is still a lot to be done. Science without Borders has been helping and Boeing, for instance, receives 25 interns from us every year. They are injecting their DNA into our youth, because they want to hire them later on here in Brazil. BP also receives a lot of our students, and at the same time they are teaching our companies that this is a necessary step.

TRC: The UK and the US believe in the future of Brazil, but how can those relationships be best nurtured?

JG: I think many interesting steps have already been taken. The UK created the Newton Fund and we have been working with the University of Nottingham. The volume of resources isn’t astronomical, but it's a start. Again, Science without Borders showed us what is possible and we have agreements with several pharmaceutical companies today for the training of our students as a result. Biotechnology is more complicated, because you can never be fully sure you will get results and we do not have a culture of risk capital in Brazil.

Even so, there has been a great focus on patents in biotechnology and there are numerous initiatives from the ministry of health and the ministry of trade and industry, through BNDES and Finep, to stimulate these partnerships. The numbers are already very encouraging as compared to ten or fifteen years ago.

“To truly internationalise, just sending students abroad isn’t enough. We have to bring others in as well.”Tweet This