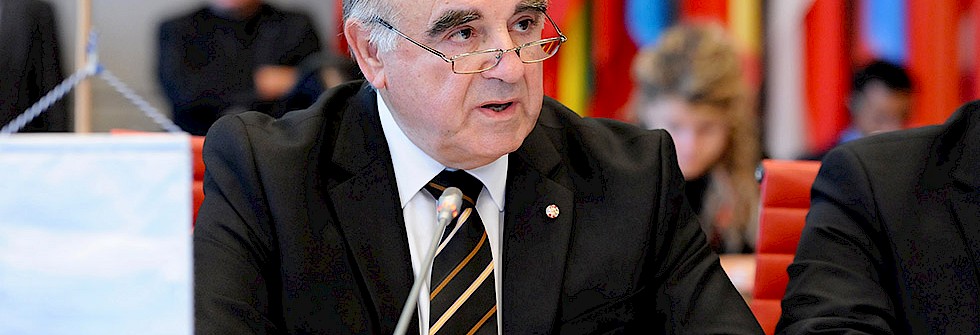

George W. Vella has been Malta’s foreign affairs minister since 2013, and during his first two years in office has been faced with a number of challenges, from regional instability to growing migration across the Mediterranean. He spoke to The Report Company about the country’s diplomatic activities and how it aims to leverage EU-wide support for the issues facing the Mediterranean countries.

The Report Company: What are the main focuses of Malta’s foreign policy?

George Vella: Malta is not in the best of situations, geographically speaking. The region is in turmoil, but one can’t choose one’s neighbours and we have to put up with the situation which has been going from bad to worse for quite some time. During the years when we had the Arab Spring, the whole of North Africa was up in flames. Now, the sequel to that is this phenomenon of migration, search and rescue of illegal immigrants from the sea, drownings, and the whole issue of how to look at this huge influx of migrants coming from Africa.

At the same time, being a member of the European Union, we have also been worried about what is happening to the east of Europe. The issue of Ukraine for us was a reality which we had to deal with and to cooperate with our colleagues in the European Union. Besides this, there was and still is the situation in Syria as it teeters on the edge of the abyss, and the effects of that conflict on further migration from Syria into Europe through Turkey and the Balkans. It’s not a happy situation at all.

All this comes hot on the heels of a very worrying period characterised by the economic downturn which started in 2008. We thought that if we could just swim through that, which we did, hopefully things would get better, but then we got to 2011, there was the Arab Spring, and since then all hell broke loose.

TRC: What is Malta’s approach to the threat of Islamic extremism?

GV: Up to now, we haven’t had the misfortune of other countries. We are not Libya, and we did not have the misfortune of Tunisia, but we are obviously very much on the alert, to ensure that we don’t get foreigners coming in who could be a threat to the security of our country, and that nothing crops up from within our multi-ethnic society. I was recently in Tunisia and one can feel that they have had a very hard blow to their tourism industry as a result of terrorism. Cruise liners are not calling there anymore, and their hotels are experiencing low occupancy. This is one of the problems. You simply cannot force tourists to come back. We look at security from this point of view and this is very important for our economy.

TRC: Massive migration from regions in conflict is making the headlines. How is Malta responding to this emergency?

GV: We have been coping with this phenomenon for many years now. As long as we could contain it, while the numbers were still small and there was seasonality about it, we sort of grew accustomed to it. We were obviously every year preparing ourselves for the summer months when we used to have a larger amount of people crossing the Mediterranean, but when things got bad after 2011, the situation worsened.

“The major issue is the tragedies that are witnessed where people just drown in front of the eyes of their would-be rescuers. We have been asking Europe to do something about this, years ago.”Post This

It has to be understood that, for us, for a very long time Libya was not a source of migration; it was a country of transit. It was mostly people coming from sub-Saharan Africa, from Niger, from Mali, and also from the Horn of Africa, where we knew full well that there were circumstances that made people leave. Many of them went to Libya when Libya was still a country where they used to be able to go to make a living and then some of them would try to cross the Mediterranean to Europe. But this was not a compulsion; it was a choice. After several years working in Libya, they would try and cross to go to Europe. So in this sense it was somewhat controlled. But then, when things started getting worse, especially after what happened in Libya, and Libya lost any central control, security or border control, it has become more compelling to leave. Recently even Libyans themselves are leaving.

What we are experiencing at the moment is the phenomenon not only of migration, but also of the smuggling of irregular migrants. People in the trade have realised that it is very lucrative to smuggle people. There is an organised flow from the south, coming from the Niger, Mali and Chad. The Tuaregs are shepherding migrants north along the Algerian border, through the Sahara Desert up to Zuwara in Libya, which is the main port of departure on the Mediterranean coast. That’s only 60km west of Tripoli. To that, we have also to add the flow of migrants coming from the east, from Somalia and from Ethiopia, and the Libyans themselves who are leaving because they feel threatened and unsafe in the fighting taking place all over the country. The point is that what used to be a flow now has become a deluge.

These smugglers are packing people like sardines into these unseaworthy boats and they are sent off to cross the sea. This is what is happening. These are not safe passages, and there are many of these boats which overturn. Others do not have enough fuel and stop halfway in the sea. Many of these people have never seen the sea before in their life and as they cannot swim, they drown. This is the challenge that we have. We used to work together with Frontex when it was organised in the past, and then when our migrant figures were increasing to really worrying levels, Italy came in with Mare Nostrum. This project was launched not only to control the borders of Europe, as Frontex does, but actually to go and search the sea for migrants. When Italy was doing that with the Mare Nostrum programme, and spending something like €10 million a month from their own budget, we experienced a fall in the number of migrants because they were being found quickly by the Italians and they were taken by them to Italy. Now, Mare Nostrum has stopped and Frontex has been relaunched, and we are already experiencing an increase in the number of migrants, to the extent that, for the first four months of this year, we already have as many migrants as we did last year, and summer is not yet upon us.

TRC: What assistance do you expect from the European Union in this?

GV: The major issue is the tragedies that are witnessed where people just drown in front of the eyes of their would-be rescuers. We have been asking Europe to do something about this, years ago. The fact that now we have a migration commissioner who is Greek and a high commissioner who is Italian helps, because they come from the region and can better understand the situation. To give credit where it is due, even Juncker himself in the electoral campaign promised to tackle the migration problem seriously. These are all factors which we are now seeing being reflected in the policies which are about to be implemented.

“We thought that if we could just swim through the economic crisis, which we did, hopefully things would get better, but then we got to 2011, there was the Arab Spring, and since then all hell broke loose.”Post This

The first is the decision to implement immediate, urgent measures to avoid a repetition of the recent tragedy where 800 persons drowned in one single incident. This is very important and this is the part that [high representative of the European Union for foreign affairs and security policy and vice-president of the European Commission] Federica Mogherini is taking care of. She is trying to put together with the United Nations a plan of action which will respect the sovereignty of Libya, even though it’s practically a failed state, while within legal parameters trying to incapacitate the business of these smugglers. This will be done by depriving them as much as possible of the method by which they’re making money, and the method is the boats that are being used to ferry people across the Mediterranean.

On the other hand, there has been the launch of a big project about migration as a whole and this is not only tackling the crowding of boats with people and then being sent to reach European shores; now we’re talking about what to do with the whole problem of migration and the plan that Commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos launched recently. This speaks about what we should do in the medium and the long term because migration is not a problem that’s going to go away tomorrow. Migration is here to stay unfortunately but we will have it more controlled, less dangerous for the people who are going to take the risk and hopefully it will be in the best interests both of the migrants themselves and of the receiving countries too.

This programme of action, this migration policy which Avramopoulos has launched, has four big divisions. One of them is concentrating on the countries of origin, and so it deals with development, industrialisation, education, and all it takes to keep people from leaving their native countries. Then there is the part which deals with the role of the transit countries, and issues such as border control. Then there is the issue of asylum, how to deal with it, and also to have an asylum policy in the sense that the European Union will have to realise that this is a resource which we can use, which we can make the best use of and it could be a win-win situation. Then there is legal migration. There are proposals such as, for example, offices in Niger where one can actually start selecting people who would qualify for privileged status right from the very beginning and ensuring that the journey to Europe is not fraught with all present dangers such as extortions, maltreatment, sexual violence, deprivation, etc.

What we are being told by the people who manage to make the crossing is that atrocious things are taking place: rape, violence, beatings, killings, etc. These people are treated like chattel. It is inhuman. We have to take responsibility because, after all, apart from international law, there is also in the context of democracy the principle of the “responsibility to protect”. We have to protect these people.

This policy on migration for the EU is a breakthrough because Malta and Italy have always been clamouring that the European Union speaks a lot about solidarity but when it comes to helping us to distribute these irregular migrants into the other countries, we don’t find any help whatsoever. Let’s be honest, it doesn’t apply to all the countries. Countries like Germany and the Netherlands have always been very helpful. Others have not. Our biggest partner in taking refugees from Malta has been the United States of America.

The European Union is suggesting an agreement which speaks of the responsibility to shoulder, and distribute according to certain criteria, the number of refugees in the other countries of the European Union. They worked out a ‘distribution key’ whereby each country is allotted a percentage of those refugees. I hope that this plan will be implemented; I hope that the countries will stick to it and that it will give results. The other important aspect of this plan is how to organise legal migration, considering that Europe needs people because demographically Europe’s population is decreasing and getting older.

“What we are being told by the people who manage to make the crossing is that atrocious things are taking place. We have to take responsibility because, after all, apart from international law, there is also in the context of democracy the principle of the ‘responsibility to protect’. We have to protect these people.”Post This

TRC: The Union of the Mediterranean (UFM) recently held a summit in Barcelona. How do you see the future of this multilateral partnership?

GV: I followed the Union for the Mediterranean from its very beginning, and in the beginning it was a non-starter. It was conceived as a political forum and it didn’t take off. The present secretary general, Fathallah Sijilmassi, is very capable and he has actually managed to project the UFM not as a political entity, but as an entity which is project-oriented. Somehow, this has worked. Apart from the fact that he removed the focus from pure politics, he has focussed on delivering, and he has been proactive in giving visibility to this institution that was on the way out. He is much respected and I think the UFM is going places. We participate a lot with him. I think the UFM is doing a good job and let’s hope it keeps going on with this vitality.

TRC: How would you appraise Malta’s international image?

GV: We are happy that Malta is doing extremely well. Our economic growth is very robust, unemployment is one of the lowest in the whole of the European Union, GDP growth of about three percent has been recorded again, and our deficit is coming down as predicted. Tourism is increasing and is reaching record levels, our gaming sector has experienced rapid growth, and the maritime sector is doing very well. A concern that we have is that all these successes could be prejudiced if there is a scare from ISIS or from other extremists in our country.

In late November we will be hosting the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, and before that we are holding the EU-African Union Summit. Later on in 2017 Malta will have the Presidency of the European Union. All this shows that Malta is doing quite well and that we are very respected in the international sphere.

TRC: What would you like to achieve prior to the end of your term?

GV: My objective would be that, before my term as foreign minister is over in three years’ time, I wish to see that the situation around us in the Mediterranean is stabilised. It is having a huge negative impact on security and stability in the region. I would also like to see Libya getting better. I would like to see it return to peace and stability. Libyans are peaceful people.

The other big issue I would like to see improve is obviously the control of poverty around the world and the unjust distribution of resources, which is at the bottom of practically all the conflicts, wars and misery that we see around us. Before the end of my term, I would also like to see a solution to the Israeli/Palestinian issue, and the successful sequence of the Middle East peace process.