A mechanical engineering professor and former dean at the highly-respected Sao Paulo State University (UNESP), Dr Herman Jacobus Cornelis Voorwald became secretary of education for Sao Paulo in 2011. His nomination for the role marked an important change in policy towards recognising the fundamental role of teachers in the nationwide push for improved quality of education following its successful universalisation over the previous decade.

The Report Company: What do you see as the greatest challenges facing higher education in Brazil?

Herman Jacobus Cornelis Voorwald: Higher education has improved greatly over the last few years, not only because of [National High School Exam] Enem, but also due to the creation of many public universities and a greater participation of the private sector. What still needs to change, however, is this system whereby the best higher education institutions are the exclusive domain of the better-prepared middle class. The underprivileged are practically excluded from good public universities, which are following the path of becoming research institutions, focussed on publishing papers. This of course benefits the development of science and in turn the population at large, so our universities play a large role in knowledge generation and dissemination, but also have to train human resources.

The most important issue for universities today is the training of teachers. Universities haven’t been able to train teachers for the new reality of basic education in the country. Over the last 40 years, Brazil has gone through a process of universalisation in education. The goal was to give every child the right to be in school. Originally it was inclusion with quality, but teacher training hasn’t kept pace with the youth of today who are now better informed and more critical, and demand a different relationship with their schools.

Today’s teachers aren’t the sources of knowledge; they have to be classroom managers, overseeing a more dynamic environment in which knowledge is omnipresent, but that still isn’t how they are being trained.

TRC: When you arrived at the secretariat of education, what first struck you about the state of the country’s education system?

HJCV: I was very critical of the quality of basic education. Previously I had been guided by the concept of meritocracy but I have changed a lot since being here, and now I am very critical of the universities. They have isolated themselves from basic education and from the role they have in a country where the majority of high school leavers aren’t going into higher education. Brazil can only develop if these young people are getting a decent education.

There are thousands of schools and hundreds of thousands of teachers in all municipalities of the state of Sao Paulo. The state system has more than four million students, and I had to go out there and see it for myself, and meet those professionals that work in it.

The system has six segments: directors, supervisors, teachers, coordinating teachers, PCNPs and employees. We have 91 departments distributed across 15 units, and I invited them all to meet with me to discuss education. Over 20,000 people participated and we received more than 6,000 suggestions across all areas, from proposals for new schools to changes in management structure, all of which helped us formulate our long-term goals. I saw how hard it is for teachers, how uninterested some people are in their children’s education, and the extent to which teachers are depended upon to teach, recover, and, if possible, not fail students.

Basic education has a very important role to play and teachers are undervalued and under-motivated because of a salary policy that obliges them to have two or three jobs. In Brazil, unfortunately, education is still not seen as valuable by some families. This is a cultural trait of Brazil, different to other countries in which, at home, you are driven towards education, because it is assumed that it is the path for development. There is no other way. In our country, education was never considered to be valuable. If we don’t change that, families will not understand the importance of them participating in the process and in turn demanding greater quality from the government.

“The most important issue for universities today is the training of teachers. Universities haven’t been able to train teachers for the new reality of basic education in the country.”Tweet This

TRC: The greatest challenge must be when neither the parents nor their child are interested in education. How can you tackle that in a country the size of Brazil?

HJCV: My own experience taught me the importance of the teacher and of exclusive education, where teachers are dedicated to providing students with educational tools that will enable them to thrive in today’s complex society. Our focus is teaching students to learn how to learn, be motivated, set goals, problem- solve, and be self-accountable.

We created a system in which the teachers received a 75 percent pay rise but were not allowed to work elsewhere or with other kids. These teachers have to really believe in the model in order to quit their other jobs and to understand that they can change the lives of these students; that it is part of their job description. Not all schools can become full-time, so we mapped Sao Paulo to establish which areas had that demand, which institutions weren’t already used morning, afternoon and night for classes, and which had a sufficient infrastructure of labs, recreation areas etc. We would find appropriate schools, then ask the community if they wanted it, thus also increasing engagement.

This model should reach around a quarter of all schools in the state by 2018. For those students it doesn’t suit, we are offering technical degree courses for when they are not in school. We need to ensure that those students who also have to work to sustain an income are given the opportunity to do their best, and that everyone has access to a good education.

This is the answer we are looking for. Not every child will have the opportunity of studying in a school following this specific model, but education needs to be about evaluating the learning process to tackle any deficiencies and provide electives that help plan the students’ lives.

TRC: What else is being done to motivate teachers who no longer have faith in the system?

HJCV: Having a good salary isn’t everything, but it is important. Anyone who says that higher pay doesn’t equal higher quality should go and live on a teacher's salary for a year and then come and talk to me. Only those who have no idea the trouble that teachers go through traveling miles to teach at the most peripheral areas of the cities, risking their lives to get there, can say something like that. Many of these teachers are harassed, assaulted, have their cars destroyed. This is our reality.

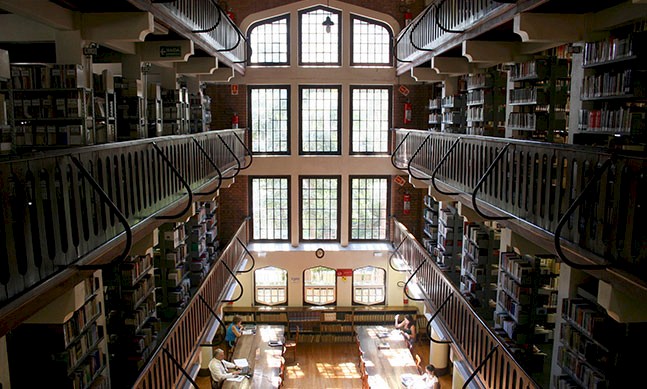

The country made the right choice by putting every child in school. The consequence, of course, is that we have blind, deaf, mute and disabled children in schools that are more than 100 years old and have neither elevators nor ramps. First we write the laws and then find a way to be able to enforce them. They create a law saying that everybody has to be in school, and then sue the secretary of education because there is no elevator in an old school that is heritage-protected. We are committed to making more than 3,000 schools more accessible in the next 15 years, which means 200 schools per year have to go through renovations at a cost of more than R$1 million per school. People need to understand that this is what universalisation means and that improvements in the education indicators are therefore slow.

“Our focus is teaching students to learn how to learn, be motivated, set goals, problem- solve, and be self-accountable.”Tweet This

TRC: Part of the government's strategy toward higher education is to let the private sector do part of the work. How do you see the role of the private sector in education overall?

HJCV: I strongly believe in the participation of the private sector in ensuring that public educational policies are implemented. Around 15 percent of basic education is in the private sector. The rest is in the public sector, whether under the municipality or the state. I think that other models, such as that of the charter schools, should be considered very carefully, however. We have to be wary of fads and I am unwavering about the fact that the state should hold the power to institute pedagogical policies, to implement them, evaluate, control and make corrections if necessary.

TRC: How important is technology for the future of Brazil’s education?

HJCV: This is a discussion that has been ongoing since I arrived here in 2011. Some people call for big screens in classrooms or a tablet for every student, but that isn’t technology, it is just equipment. The path we have chosen is a platform called Curriculo+, in which our 75 technology teachers curate learning objects that are then disseminated to the state as a whole. This year our teachers will begin making and posting content to it. Sao Paulo’s state-wide syllabus is very important in that respect, and because the platform is available to every teacher, its growth has been amazing. Now, good classes in all disciplines are available.

TRC: As a professor first and foremost, was your appointment an indication of the government taking a new direction in its education policy?

HJCV: I believe that education should be in the hands of educators, and not be used as a political stepping stone. We need focus. When education is used as a political tool, you create that feeling within the system that nothing solid is being created, which is not good. The system needs to have credibility in what it does, to have achieved goals. I believe that as a country we are doing well, but culturally we need to recognise just how precious education is.

“Anyone who says that higher pay doesn’t equal higher quality should go and live on a teacher's salary for a year and then come and talk to me.”Tweet This