The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) was founded in 1951 with the objective of promoting scientific research across Brazil. A key element of its work has always been the promotion of international knowledge sharing and exchanges, building partnerships that the new president, biochemist Hernan Chaimovich, is in no doubt are the key to great global innovation. Equally important for the country’s future, however, is the encouragement of entrepreneurialism so as to lay a more fertile and receptive groundwork on which Brazilian academia can flourish, society can be more inclusive and the private sector can be competitive in the world market.

The Report Company: What is your appraisal of the education sector in Brazil and what challenges lie ahead?

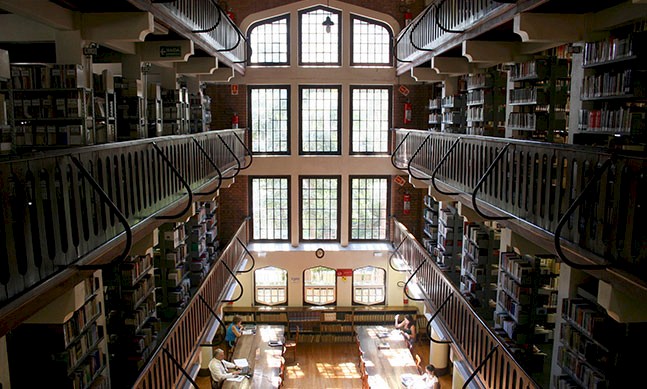

Hernan Chaimovich: There is a whole spectrum of institutions that call themselves universities in Brazil. If we define a university as an institution capable of training PhDs, the first in Brazil was the University of Sao Paulo (USP), founded in 1934, centuries after the first universities in the world. Higher education in Brazil is very recent.

Before USP, the state of Sao Paulo had schools of medicine, engineering and agriculture, all separate from one another and with no research mission. In 1934, USP incorporated the traditional schools and created a new faculty of philosophy, sciences and letters (FFLCH). The mission of FFLCH was to train students in parallel with intellectual creation, academic critique and research in all areas, from languages and literature to physics. The goal was to disseminate the idea of research throughout the system.

At the same time, the coverage of basic education and high schools was extremely limited. It was impossible to imagine that Brazil could be a developed nation, complete with well-developed agriculture and industry, without adequate basic education coverage and universities of that type. Despite all of Brazil's current problems, economic and political, anyone can see that a true revolution took place since 1934 in terms of the training of human resources.

There are still sectors which lack professionals, but many do not. Pre-salt oil exploration, for example, would have been utterly impossible without engineers, scientists, mathematicians and technicians of all levels. Without our agricultural research, we would never have become one of the most important food exporters in the world. People think that we are only able to export soy because we have a lot of land available, but the amount of technological development that has gone into our agricultural revolution over the last 40 years is massive. None of that would have happened without Embrapa, without the Luiz de Queiroz School of Agriculture, without technicians that could operate top-notch million-dollar agricultural machinery.

TRC: With regards to patents, there are those who think they should be held by universities and those who think they should be in the realm of the productive sector. What is your stance?

HC: In the US, probably the country with the greatest number of academic patents, the first university appears at something like number 200 in the list of top patent producers. All other patents are registered by companies like Apple, Google, pharmaceutical companies, biotech start-ups and the like.

I believe that we have the conditions for innovation to emerge where it occurs naturally, that is, the factory floor, independent of the type of factory or the type of floor. That doesn’t mean universities should not hold patents, and they need to be aware that part of their creative work is indeed patentable. But the path from patent to product is long. The University of Sao Paulo is the third largest applicant for patents in Brazil. I am not saying that this is bad for USP, but it doesn’t make sense for the country. Our investments into private R&D are strong, but their efficiency is relatively low.

We will be internationally competitive and Brazilian companies will produce for the world market and innovate when the number of patents registered by companies increases. At the same time, universities have a duty to look at their intellectual production and see which parts need to be protected. The goal is not to turn the university into a factory, but for it to get back part of what it invested.

Entrepreneurialism also has to be incorporated into the ethos of universities, and I believe that this is growing. For instance, in the biomedical sector in the United States, many discoveries result in startups which may grow and be purchased by a larger company which then makes the necessary investments for it to thrive in its own right. This is a very healthy attitude and one that is growing in Brazil, but the conditions here are different and our capital funds don’t take as many risks. The public sector then has to take its responsibility and make that commitment of taking the risk.

“The amount of technological development that has gone into our agricultural revolution over the last 40 years is massive.”Tweet This

TRC: What is your take on the relationship between the state and the academic and productive sectors, and where does CNPq fit into this?

HC: I became president of CNPq rather recently. Before that, I worked for four years at Fapesp, where we signed extremely interesting partnerships with the likes of British Gas, Natura and GSK. I would like CNPq to become a centre for discussing strategies. How can we stimulate research in all areas aiming at the intellectual, social and economic development of the country? This implies a level of autonomy that allows long-term planning. It is impossible to design development strategies within a short timeframe. One can only design development strategies properly with the future of the country in mind. To do that, agencies need to be autonomous, think strategically and invest over longer periods of time.

The healthy and extremely fruitful relationship between the presidency of CNPq and the ministry of science and technology - especially the minister - will allow me to take on my political role exclusively. I do not have to coordinate only with ministers, but also with ambassadors, senators, congress members and governors. The role that the president of CNPq needs to play is, essentially, a political one. It is also about representation.

TRC: Everyone is talking about Brazil becoming more competitive, but what are the key areas that require most attention to make that happen?

HC: CNPq needs to look at science from two different points of view. Firstly, its intellectual impact, which means we have to have ideas that generate other ideas, both in Brazil and abroad, in philosophy, high-energy physics, education, molecular biology, theoretical chemistry, and so on. Secondly, we need to create the conditions for knowledge to produce social and economic impacts.

Brazil is the only country in the world with water, energy, a population of 200 million people and a continent-sized territory. With that in mind, what can we be competitive in? We will be competitive in food, water and energy - they are strategic and we will invest in those fields. Despite the current water crisis, it would be very hard to convince anyone in North Africa that we lack water or that our biodiversity is low, or to try to convince people in China that there is insufficient land here on which to plant crops or have energy sources.

If we produce traditional and alternative energy, it is very easy to foresee the implementation of a nationwide intelligent grid, which will leave us with a serious problem: excess energy. The grid would be fed by wind energy in Ceara, by hydroelectricity in the south or the Amazon, by the sustainable use of sugarcane bagasse in Sao Paulo, and there would be an excess of energy. The grid isn’t ready, but we will get there.

If we have an excess of energy, how can we store it? This is an unsolved scientific problem. If we do not, for instance, invest in the chemistry of batteries or in the production of hydrogen, we won’t be able to store it. An overall project in sustainable agriculture, water and energy involves mathematics, chemistry, the social sciences, ethics, architecture and everything else. What I'm saying is that yes, we can design pervasive, transversal strategies that meet the country's strategic needs, that makes us internationally competitive and promote the need for training and research in all knowledge areas, of which one is water and energy.

“We will be internationally competitive and Brazilian companies will produce for the world market and innovate when the number of patents registered by companies increases. At the same time, universities have a duty to look at their intellectual production and see which parts need to be protected.”Tweet This

TRC: How crucial a part does the internationalisation of Brazil’s higher education institutions play in the country’s long-term strategy?

HC: We have a gigantic responsibility to increase the impact of our intellectual production. Internationalisation is one way to do it. When scientists from different places can talk about the same issue in the same language, but coming from different cultural backgrounds, they are able to create projects with unimaginable proportions. This happens when Brazilian scientists sit together with scientists from India, the United States or Chile. Creating international research partnerships results in much more knowledge creation than the sum of its parts; it has a multiplying effect. Research internationalisation, for me, means creating together. Brazil has the conditions, the density and the scientists in all knowledge areas to allow this sort of development of new ideas. It would be impossible to create these ideas based on a single point of view.

I’m talking about research, not simply exchanges of people. The Science without Borders programme, especially at the undergraduate level, is an entirely different question. On average, Brazilian universities are extremely conservative in their structure and in the ways they teach and educate. These kids come back from abroad to something they don’t recognise anymore. There, they didn’t simply sit for eight hours a day listening to a teacher; they had entirely different experiences. They worked much more on their own, the other classmates did not turn a critical eye on them when they wanted to ask a more searching question. This international experience has been showing them that they can work better with fewer classes and that their productivity will not be diminished. If we could work on these two fronts in our universities, we would gain a lot.

TRC: What is the role of CNPq in the economic development of the country and what are your immediate goals?

HC: My goal is to open up CNPq much more to the private sector. We have to ask the private sector what it needs so that their demands and our research mission are aligned. Based on experience I have no doubt that this is possible. When you reach a frank level of dialogue that respects the different mission of both parties, and you are able to identify common goals, both private companies and universities can participate on win-win agreements.

“We have a gigantic responsibility to increase the impact of our intellectual production. Internationalisation is one way to do it.”Tweet This