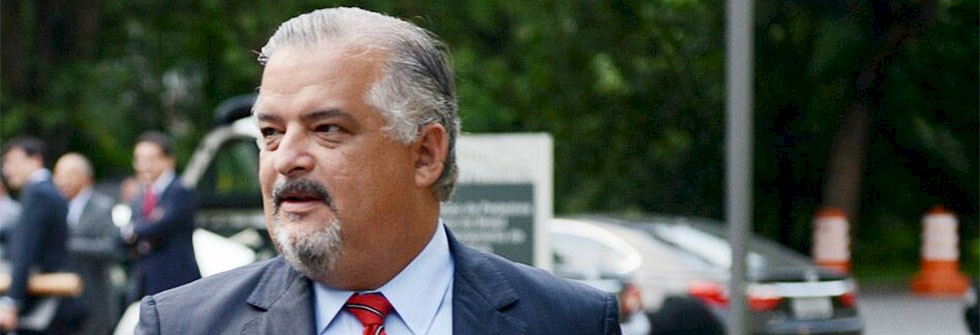

Alongside the state’s longest-serving governor, Franca has been instrumental in steering the population through a headline-grabbing energy and water crisis and public security worries. A groundbreaking programme to help push the region’s disenfranchised youth towards positive social involvement set the tone of Franca’s goals for the administration, along with a greater emphasis on the creative industry to strengthen the economy. The Report Company met him to find out more

The Report Company: Brazil has had a hard time on the international investment stage recently, but what is the financial situation in Sao Paulo? Is it as hard as in the rest of the country, and how do you see 2015 shaping up from an economic standpoint?

Marcio Franca: Economics is like politics: the expectations are stronger than the facts. President Lula was a skilful politician and was able to create an air of expectation. He was like a conductor producing this overall positive feeling, playing several instruments very well and conducting the orchestra with magnificence.

Yet today, Brasilia communicates an environment of instability to Sao Paulo, and although we represent almost 40 percent of the economy of the country, the state is a patchwork of national forces and is able to stand stronger on its own. Since 1906, not a single president has hailed from Sao Paulo. It is the other states that have had to be more boisterous while our economy has remained discreetly strong. In my view, instability will force Brazilians to demand stability. Things have been a mess for too many years. You turn on the TV and it is scandal after scandal.

Governor Geraldo Alckmin is the complete antithesis of that and people recognise that stability. It fits Sao Paulo perfectly and that is why he was elected for a fourth time, more than anyone else. But Brazil is bigger than Sao Paulo, and the country has to do well, too. I believe we should be betting on the creative economy and smaller companies. Because of the water and energy crises, it will not be as easy to attract big companies. In this context, we need to work on solutions for smaller-scale investments.

TRC: Why do you emphasise the creative economy?

MF: It's a hunch, but based on facts, of course. Brazilians are very creative, largely because of the hardships they have had to go through. During hardship, people move around, learn a little bit about everything, but that needs to be harnessed. More emphasis on the creative economy doesn’t have to mean deindustrialisation, but, for obvious reasons, industries today employ fewer and fewer people. Humans are almost irreplaceable in the creative economy.

There are numbers in Brazil that are strikingly negative. Brazil receives fewer tourists than Uruguay. This cannot be correct; there has to be something wrong here. There is a lot of room to grow, with the added benefit that we do not have to wait for anyone to get here to do it. We can work with what we have and incentivise small agencies to come here. I believe that the solution for us is intrinsically linked to small endeavours, and that there is a lot to be explored here.

“There is a lot of room to grow, with the added benefit that we do not have to wait for anyone to get here to do it.”Tweet This

TRC: The UK ambassador to Brazil said that the two countries have two main fields to work on together: education and culture. Can these relations be used to build further links?

MF: I believe that something like this is very likely. The profile of the English is very different to that of Brazilians, but the two countries can have very good relations. When you look at it, there’s a great amount of history there. Portugal was always very close to the UK, and we have an obvious relationship with the country. Large educational groups from the United Kingdom have already come to Brazil to purchase Brazilian educational institutions, so there is something there already, too. The standards of English education should be followed, clearly, but on the other hand, we have to find — in all our physical vastness — something that could serve them.

We do not have a model. Brazil has always been uncoordinated about having such a strategy. Historically, we had a long coffee phase but we never thought about the instant coffee market, for instance, so we just exported coffee grains, which is easier. Today, we export US$3 billion a year in leather and produce US$1 billion worth of shoes. There's something wrong with those numbers. We should make more shoes and sell less leather. India and China scared the productive world a little bit. In Ceara, the Padre Cicero figurines are now made in China. The traditional lacework from Ceara was substituted by Chinese products. This scares people. However, as we predicted, China will start having its own problems now because of the strength of democracy, knowledge, education, the demand of certain labour standards, and so on. Every country has had to go through that.

TRC: Regarding education, what were the results of your Neither/Nor programme designed to stop kids from falling out of school? Can its success be expanded?

MF: We are currently entering a phase in which the most important demand is for the improvement of public services. Those who are able to provide that will be successful. However, one thing that scares the middle class is the feeling that they are helpless against violence. Fifteen or sixteen-year-old boys — exactly when they have to make decisions about the rest of their lives — are very vulnerable and have no perspective. The poor think they don’t stand a chance. Society reacts with violence as well: arresting, imprisoning, aggression.

Former ambassador and minister Jose Gregory suggested that I use an article of the constitution regarding civil enlisting. It is like military enlisting, only it is for civilians and it isn’t mandatory. We created a mechanism to invite those boys in vulnerable conditions to serve the municipal government, paying them for their work. They worked for us for four hours a day and were obliged to do a technical course while they were with us. There are other programmes like that in the country, but the difference with this was that this wasn't just a few kids, it was all of them. For the 2,500 boys and girls who turned 18 that year, we identified 800 as vulnerable, and we hired all of them.

When they are together, they feel like they are part of a whole, they feel strong and have their self-esteem back. They used to be outcasts, but now they are wearing uniforms and they feel like they turned things around. It’s funny how the most undisciplined become the most disciplined. They are the most rigorous and they love the feeling. We called them municipal coordinators and they walk around in uniform with walkie-talkies and are trained in several different aspects over 45 days: tourism, culture, road safety, traffic, first aid and things like that. Their presence gives people a feeling of safety.

The rationale is the same as that of a politician in the second round of voting: if I take one vote away from you, I get two votes. When I take kids away from the possibility of violence and bring them to my side, not only I get their presence on the streets, but they also are not doing anything wrong on the other side. We started feeling that the indexes of violence in the city were dropping fast. When we discussed the political arrangement with the government to have our party on board, I suggested this programme to the governor. He agreed to it and we put it in the government programme.

“We are currently entering a phase in which the most important demand is for the improvement of public services. Those who are able to provide that will be successful.”Tweet This

TRC: Such programmes are clearly of vital importance for the country’s future. What can Brazil still offer to the international market at large?

MF: I have no doubt that Brazil will be a very promising surprise. We are capable of overcoming difficulties very quickly. It seems like it is very far away, but investors do not invest with a single semester in mind and I think there will be great opportunities in the mid-term. It’s not about finding new paths but improving the ones we have. The creativity of Brazilians is almost uncontrollable; we will find solutions, one way or another. Our weaknesses are our qualities.

“Brazil will be a very promising surprise. We are capable of overcoming difficulties very quickly”Tweet This