The long-running argument over private sector involvement in higher education is slowly dying out as the new breed of universities brings education to Brazil’s demanding masses for the first time

In 1968, in a bid to modernise Brazil’s rigid, modest higher education sector, the government issued a much-needed reform of universities to ease the process of inaugurating new courses. There was an implicit understanding that, without private sector investment, a crisis in the population’s educational development was inevitable. Throughout the next decade, large private groups like Uniban and Estacio emerged onto the market, but even so, in the 1980s, enrolment into university didn’t even keep pace with population growth and the burden of the past remained.

It was ony in the mid-1990s, when the law was liberalised to allow private entities to profit from education for the first time, that the democratisation and privatisation process of the sector began. There followed the provision of grants and bursaries that saw increasing places and interest from private investors. As money flooded the sector, it was suddenly able to innovate, react to the changes in technology in a way that public universities could only dream of, and, as acquisitions and mergers consolidated the sector yet further from 2007, bring an entirely new economy of scale to higher education.

“While the number of places has increased, the quality hasn’t. In the dangerous situation Brazil was and still is in, quantity must come first, but we cannot wait too long to address quality”

Rogerio Melzi CEO of Estacio Participacoes

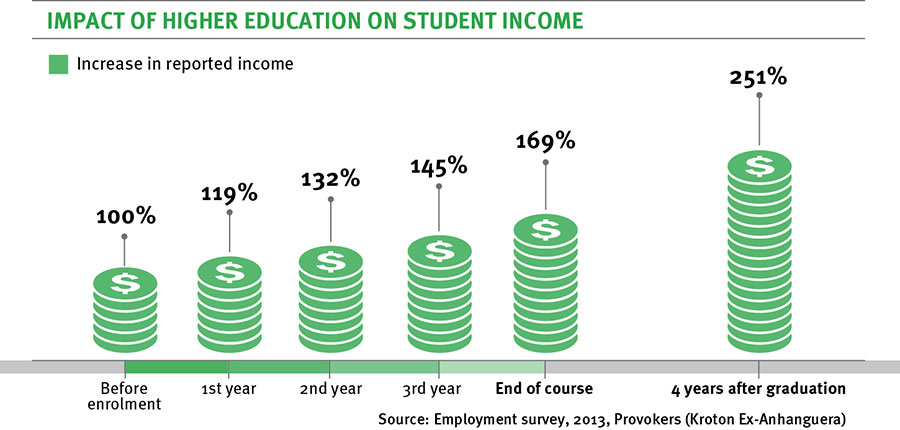

Post ThisThese new universities saw the traditional institutions as bloated and inefficient, overly focussed on research and out of step with the demands of the 21st century. In response, private universities were accused of prioritising quantity over quality, but while the sudden mixture of backgrounds and abilities has proved challenging, there is a clear pattern towards a greater diversity of graduates entering the job market better prepared than ever before, and that can only benefit Brazil.

Education versus profit

The sharp rise in university places over the last quarter of a century has largely been thanks to the private sector, but the argument that this represents opportunistic profiteering is only now being put to rest. The higher education mass market is buoyant, and though the wave of acquisitions has rung alarm bells, the sheer demand – and its immediacy – would render such growth impossible if left to the public sector. Scale was always the government’s major stumbling block, but this is university education for the masses. Consolidation has meant profits, but also private-sector efficiency, and competition will always be strong enough to mean that companies like Kroton and Estacio will have to pump money back into their structures in order to build the reputations they crave.