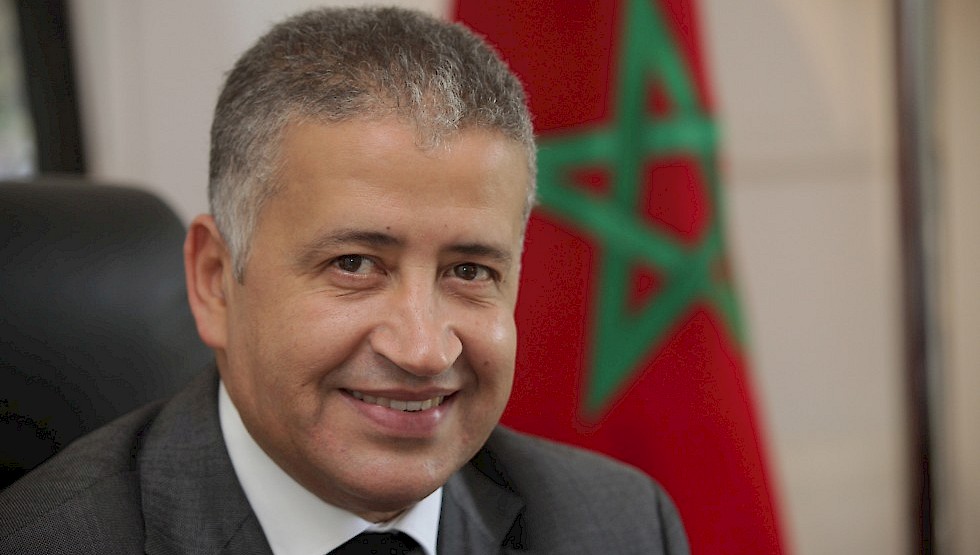

Lemghari Essakl, who leads the Bouregreg Valley Development Agency, spoke to The Report Company about the development path Morocco has chosen and the opportunities available for foreign investors to participate.

The Report Company: How would you appraise Morocco today?

Lemghari Essakl: Morocco is part of the MENA region. It is also extremely close to Europe. During the reign of Hassan II, there was an official request from the country to join the European Union. This was somewhat daring of the former king, but in fact he was ahead of his time. He predicted many phenomena that have been proven to be correct, especially in terms of the economic and social links that the North African countries could develop with the southern part of Europe.

Hassan II’s dream was not fulfilled, but we have the privilege of having favorable agreements with the EU. Morocco has also signed free trade agreements with the United States, Turkey and the Gulf Nations.

History has been made in Morocco with the accession of King Mohammed VI, who has distinguished himself with the quality of his governance as head of state, establishing security for the region. In Europe, there have been several changes, and it feels as though the situation has not yet stabilized, and we have seen several economic problems in France, in Spain, in Greece and in Turkey.

We have been very fortunate to have a good dynamic with Mohammed VI. He cares about all of the economic sectors and opens us up to the world while addressing certain difficult areas. As an example, the creation of the “equity and reconciliation” body allowed the Moroccan regime to tell the truth about a very difficult period where there was disagreement between the highest political levels and certain political fringes, both recognized and clandestine. The king has found the right way to get the whole of Moroccan society on board with his plan for Morocco to be one of the emerging Mediterranean countries.

“The idea is to make Rabat a capital worthy of the name which can compete at the Mediterranean level and be considered a city of knowledge, enlightenment and culture”Tweet This

TRC: What impact have the financial crisis and the Arab Spring had on your projects?

LE: We must be careful with the words we use, particularly with regard to the crisis. Morocco has always had good relations with the Arab countries of the Middle East and the Gulf. We have always had good relations with our neighbors, even with Algeria which is a very different country from our own. The Gulf countries which are able to invest directly abroad have always had a privileged relationship with Morocco, before the Arab Spring, and things have not changed because of this Arab Spring. Morocco has always been considered as a stable destination whose culture can adapt to that of others.

We carried out the feasibility study on our project in 2002, based on the founding principles that are universally known and adopted by major urban developers. Environmental protection is a major axis for us as well as providing all necessary infrastructure for a harmonious urban development. It happens that this space, upon which we began work, is near to the Moroccan capital, located between two imperial cities – the city of Saleh which is on the right bank, and the city of Rabat. The valley has always been considered as a border between the two cities. The idea therefore was to develop an urban space to unite these two imperial cities and generate prosperity for their ever-increasing population. There are 2.5 million inhabitants, which is a very large number; while we are not in the economic capital, which has over 4.5 million inhabitants today, we are in a zone which is considered as a provincial capital.

The idea is to make Rabat a capital worthy of the name which can compete at the Mediterranean level and be considered a city of knowledge, enlightenment and culture.

The project carries several messages. It is financed, and has been from the beginning, by public funds, coming from the state and the general budget as well as from funds such as the Hassan II economic and social development fund. This is a fund that was set up at the end of the 1990s by the late Hassan II and which is partly fed by privatization revenues. Our project is also financed by the general directorate of local government, which is a central department at the ministry of the interior, and which gets its resources in part through the VAT collected nationally. When we started the development of the Bouregreg valley, it was never a question of relying totally on foreign money.

“Our objective is to choose a good partner and help them to succeed.Tweet This

If they don’t succeed, our reputation suffers”

TRC: Have you approached foreign investors?

LE: In May 2005, the emirate of Dubai approached us after a visit by the Sheikh Mohammed Rashid Al Maktoum to the Tangier-Med port. On the sidelines of his visit, as he has a residence in Rabat, he expressed the wish to learn more about our project, which was just getting started. He was given an overview of the project, and following that, he sent a delegation to explore the possibilities of development opportunities with us.

So, we conceded to them a part of this territory. On the 6,000 hectares, we had identified a small, 100-hectare parcel, on which they expressed a wish to launch a major operation that would be a housing complex with everything that you could imagine in an urban center: hospitality, residences, offices and others. That began in 2006. The concept of the city, the buildings, and the public space was based on the purchasing power in Dubai.

However, this project couldn’t work because we couldn’t develop in Rabat what you see in Dubai: the skyscrapers, the tall buildings, the American-style urbanization. We are a country with a centuries-old history and with abundant nature; we can’t change our territory for the worse. That much is clear. On 7 January 2006, his majesty said “I don’t want the Dubai model here. It is not suitable to our culture”. And so the decision was made.

Then the crisis came, which hit Dubai harder than the other emirates. It also hit Europe hard. Why do I mention Europe? Because with these projects here that are two hours 40 minutes from Paris, an hour and a half from Madrid, and an hour and five minutes from Portugal, we were hoping to open ourselves up to Europe and reap the rewards of marketing ourselves to certain individuals who could invest here with us. Unfortunately, Europe today has crashed and I don’t see many French households, for example, with extra cash to come and buy a second home here.

So, because of all of these factors, the first attempt with the emirate of Dubai was not successful.

Meanwhile, we have the emirate of Abu Dhabi, which is our real long-term partner, and Saudi Arabia, who we have built up a relationship with over decades. These might, for you Westerners, seem like one-way relationships, but Morocco has been a great help to Saudi Arabia. What’s more, up to the beginning of the 1980s, Abu Dhabi didn’t have the wealth it has today and there were many things which went from here to there.

Capital goes where profit is, except in the case of state-to-state aid. But, as far as we are concerned, for the movement of capital from these countries, be they Qatar, Saudi Arabia or the emirate of Dubai, they come to invest in a certain number of activities that generate returns and we know full well that no-one is coming here to give us something for nothing.

So, they are there, they have their strategic development plan, they have a business plan in mind thinking in terms of a return on investment for their own funds. Sometimes we encounter difficulties with some of them because they set the stakes quite high, and aim for double-digit returns, whereas today the returns, no matter where you put your money, are still around three to five percent. You have to be realistic.

Our objective is to choose a good partner and help them to succeed. If they don’t succeed, our reputation suffers. We need to avoid that. We need to make sure the projects are feasible and suitable. We’re not looking to bring in investment for which there aren’t any returns. I’m delighted to see that in the automobile sector, Renault has come, and they are doing well, and now we have Peugeot, too. We may have another firm soon. That’s good business and a good relationship.

“Morocco is a country in the making. The term ‘emerging country’ doesn’t correspond completely to the economic reality of today.Tweet This

We need a little bit of time”

TRC: What kind of profile are you looking for in an investor?

LE: A good investor is one which is able to get to know the territory and the culture and who is here for the long term.

There are two types of investor: those who do a quick pit stop in a place, and those who sign up for the long term, and who are strong enough to go the distance.

These are the investors who have their investments with us for the long term, for example the investors who are backed by pension funds and so on, who have the resources to place in a country which is economically and politically stable. These are the investors who can build upon the future of a country.

Morocco is a country in the making. The term ‘emerging country’ doesn’t correspond completely to the economic reality of today. We need a little bit of time. Things are taking root, but we need investors who understand that. And we must also count on Moroccan investment. We are seeing the emergence of wealthy Moroccans who are specializing in several economic sectors and which could be interested in these projects.

TRC: What makes the Bouregreg project stand out?

LE: Our project stands out because from the very beginning we adopted a social and land management strategy to make sure we add value progressively to each part of the area. For example, when we started, we developed a town called Marina Morocco (formerly known as Bouregreg Marina) but which was actually called Bab al Bahr. We did this development in an area which was worth nothing at the time. We have turned this territory into something valuable. At the beginning it was just a huge swamp, there wasn’t a marina or anything. We created a private entity, which was an offshoot of a public institution. We opened up its capital and brought in foreign investors. This allowed us to identify a significant resource, of around €100 million, which enabled us to develop our efforts in infrastructure and protect another zone from flood risks, give it an urban plan, and in this way, also make it profitable.

The project is unique because one of its primary concerns was the question of mobility. Our thinking is that modern urbanization cannot be successful without taking into account the movement of people. That’s why we have put so much effort into infrastructure projects such as the Udaya tunnels and the Rabat-Saleh tram which is just beginning; it’s 20km now but will soon be extended into other neighborhoods.

TRC: Is your investment focus mainly on transport?

LE: We have money from the state and local authorities as well as the Hassan II fund, and we have been told: “be careful, you are going to put all the money into mobility and you won’t have anything left for real estate development”. But I believe that the private sector should do the real estate side of things, and we should prepare for them development platforms and reassure them about the future because there are areas that are opened up to urbanization without a long-term vision and end up with bottlenecks and problems. We decided to put 80 percent of our resources from the very beginning into maritime transport, making the river navigable with a border post, infrastructure projects, the Udaya tunnels, the roads, and 20km of tramline. This is around €700 million, so not a small amount.

We have also even signed partnership contracts with very large investors, who believe in us and our way of approaching institutional, judicial and technical problems. These include the French Development Agency (AFD), the European Investment Bank, French state funds through the Reserve emerging countries program, and we have even benefitted from the EU Neighborhood Investment Facility. The Rabat-Saleh tramway is the first project in the South Mediterranean to benefit from this facility, which is normally destined for the Balkans and the Eastern European countries, but when the EU saw what was happening here, they provided us with around €8 million which has enabled us to carry out the project and finance the tramway extension.

TRC: What would be your message to potential investors?

LE: When someone is investing abroad, they want to be welcomed, understood and helped to set up their project. We understand that, and Morocco has been a pioneer in the field of putting in place organizations and mechanisms that facilitate access to Morocco itself – such as the free zones and the industrial zones which are set up to receive these investors. The country has also put in place one-stop shops to facilitate business creation with as few delays as possible. Then, Morocco also needs to be prepared to have a framework of employees, of workers, of people of all skill levels to help these enterprises to develop here.