Progressive reform is now underpinning the country; Morocco’s transition toward a diverse modern economy is taking root

Morocco’s strong domestic economic landscape and its embrace of free trade has seen the country develop almost unrecognizably in social and political terms over the last 20 years, backed by average economic growth of 4.36 percent since 1999. Thanks to a combination of solid, long-term politics and essential constitutional reform, the country is settling down to a new business climate and entrepreneurial spirit. The country is finding new markets in Europe, the U.S. and the Middle East, while continuing to provide a gateway to its partners in the huge, developing markets of the African continent.

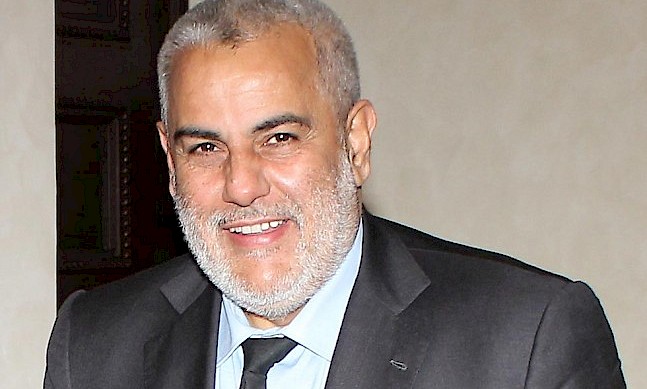

In recognizing equal opportunities, cutting poverty rates by almost 50 percent in the last decade and instituting the Arab world’s most progressive family code reform to raise women’s interests, King Mohammed VI helped Morocco sidestep the worst of the Arab Spring. That paved the way for a new constitution in 2011, with Abdel-Ilah Benkiran brought in as chief of a coalition government in which 17 percent of politicians are now women, up from just one percent at the turn of the century.

“Morocco’s economic growth has averaged 4.36 percent since 1999,Post This

and poverty rates have fallen by almost 50 percent in the last decade”

As well as restoring the social equilibrium, Benkiran’s moderate government is determined to stimulate business, encouraging the private sector to invest in promising new sectors to foster entrepreneurialism in all regions, not just the urban centers. Today, it takes just 10 days to set up a business in Morocco compared with the regional average of nearly 19. “I believe that the government should disengage itself from all of the sectors that the private sector or civil society would take better charge of,” says Benkiran, “and refocus the available resources towards the citizens, the sectors and the regions that need them most.”

Since forming his government, Benkiran has been able to proactively shape Morocco’s own destiny thanks to the king’s efforts that he says demonstrate “both the determination to guarantee the stability of our country and the will to respond to the desires of the citizens in terms of widening the democratic space, strengthening justice and reducing inequality.”

Having created 100,000 jobs at the halfway stage alone, the 10-year, $2 billion commitment of the Emergence Plan to boost industrial development came to its conclusion in 2015 having successfully provided the stimulus for new industries to establish themselves.

Traditional sectors have also flourished, such as the automobile industry, whose exports are set to top $10bn by 2020. Agriculture may still account for 15 percent of the economy and employ 40 percent of the workforce, but it has modernized in tandem with the high-tech aeronautics, pharmaceutical and communications industries. These are contributing to reducing the fiscal deficit and encouraging a boom in foreign direct investment.

A new law governing public-private partnerships, introduced in 2015, has helped facilitate the development of infrastructure projects. This looks set to play a significant role as Morocco looks to resolve its complex energy mix through investment in its largely untapped oil reserves – a charge led by the National Bureau of Petroleum and Mines (ONHYM) – and the development of renewable energy supplies. At the same time, the pharmaceutical sector has been naturally stimulated by the move toward wider adoption of health insurance, helping companies like Laprophan to establish internationally and domestically as the government pursues 80 percent healthcare coverage by 2020.

Nizar Baraka, chairman of Morocco’s Economic, Social and Environmental Council (CESE), puts much of the success down to free trade agreements with the likes of the E.U., U.S., Canada and the Arab League, and the provision of attractive measures to stimulate investment. According to Baraka, the goal is to “consolidate the role of Morocco as an investment and export platform for Africa, Europe, the United States and the Gulf countries.”

Achieving that goal means targeting Morocco’s young workforce. With nearly 20 percent of the population aged 15-24, investing in training and English language skills is part of what Baraka calls “an intense catch-up effort” needed in education, connectivity, welfare and access. Human capital has been identified as a fundamental axis on which growth will hinge, and the Office of Vocational Training and Job Promotion has already laid out a vision to provide women and young people the opportunity not just to contribute to the economy but to innovate within it.