Sithe Global, a power development company owned by funds managed by investment firm Blackstone, developed and brought to fruition the Bujagali Hydropower Project. Named Africa Power Deal of the Year 2007 by Euromoney’s Project Finance Magazine, the project is a 250MW hydroelectric facility on the River Nile. Company president, Brian Kubeck, spoke to The Report Company about why the firm chose Uganda as an investment destination.

The Report Company: How big a project is Bujagali to Sithe Global?

Brian Kubeck: It depends on how you measure it. If you measure in megawatts, you could say it was small, but in terms of capital investment and the importance to the company, it’s right there with all the others and one that we’re particularly proud of just because it really was a bit of a ground breaker in Africa.

TRC: Why did the company choose this project?

BK: Sub-Saharan Africa is a pretty exciting part of the world right now. There’s so much focus on it via initiatives such as Power Africa. The lack of access to power is such an inhibitor to growth. To us, that has presented an exciting investment opportunity, so with Blackstone’s capital and Sithe’s expertise, we bid aggressively for Bujagali.

Blackstone has now invested $25 billion in greenfield projects around the world, some of that through Sithe, and some of that externally. They created Black Rhino, which is dedicated only to sub-Saharan Africa and primarily the energy sector. This is a huge sign of how important Blackstone views this market as being. Blackstone recently announced a partnership with Dangote Industries, one of the most successful companies in Africa.

The bottom line is that 70 percent of the population of sub-Saharan Africa does not have access to electricity. It’s widely agreed that GDP growth rates would be over seven percent if there was access to electricity.

When we looked at Bujagali it had to fit in with our key criteria, and one of those keys was putting together a least-cost project, so at the end of the day we were able to deliver a project that had an average cost over 50 years of 6.6 cents per kilowatt hour, with 1.6 cents of that going right back to the government in the form of taxes and other government revenue streams.

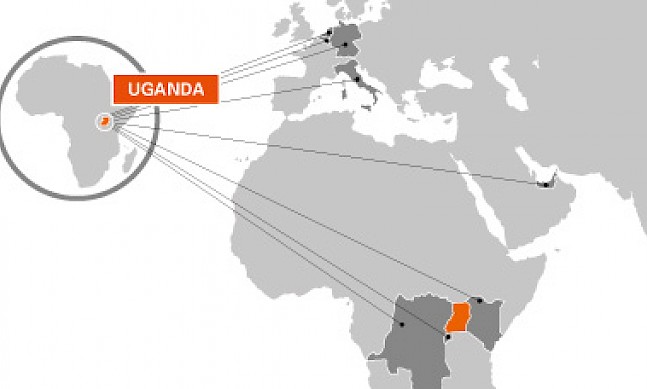

Another key when selecting the host country is ensuring it has good rule of law, transparent processes and an investor-friendly environment. There also has to be a need for the project; it can’t just be a pet project, it has to make good economic, environmental and social sense.

You have to be able to put the project together in a socially responsible way so that it’s good for the environment and it’s good for the country. We offset 900,000 tons a year of CO2 emissions and that makes Bujagali the largest renewable clean development mechanism (CDM) project in Africa. It also makes Uganda stand out in that 90 percent of its grid is sourced from renewable energy, which is something that not too many countries in the world can say. At the same time, we reduced power costs in Uganda by 66 percent the day Bujagali came online.

TRC: How do Blackstone, Sithe Global and Black Rhino work together in Uganda and the rest of Africa?

BK: Sithe Global and Black Rhino work closely together and will continue to do so. We are both entirely owned by Blackstone, so we are sister companies and there really isn’t any competition between us. We cross resources all the time. Ultimately, I would expect Black Rhino to be the primary development vehicle for sub-Saharan Africa, but there is significant support from Sithe Global of Black Rhino activities, so there is significant crossover.

TRC: How do you view the public-private partnership (PPP) model as a means of providing Africa with the infrastructure it needs?

BK: Africa has its challenges, but for us it’s an exciting place. One of the biggest challenges is that it has historically not had very good access to capital. It has had access to public financing and donor financing, but not big sums of private capital. This means you just don’t get the benefit of private expertise, which is certainly significant, and also there’s just not nearly as much capital if you exclude the private sector.

When you take Bujagali, that was $900 million that would either have had to come from the government or from the private sector and if it came from the government, that’s $900 million they couldn’t use for other development projects that would help the country move forward. From our perspective, the PPP approach has a lot of benefits for the host country and it’s exciting from the perspective of an investor because there are not a lot of places in the world where you can combine the goals of a socially rewarding investment with a financially acceptable investment as well.

The PPP model in sub-Saharan Africa enables you to bring together a lot of pieces and get a lot of projects off the ground that the private sector alone would not do and that governments alone would never be able to do due to prioritization of resources.

“There’s the need for broad and strong support for a project from the government, which we had in Bujagali.”Post This

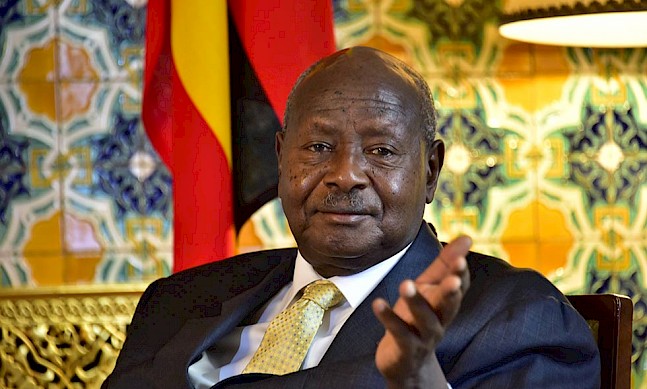

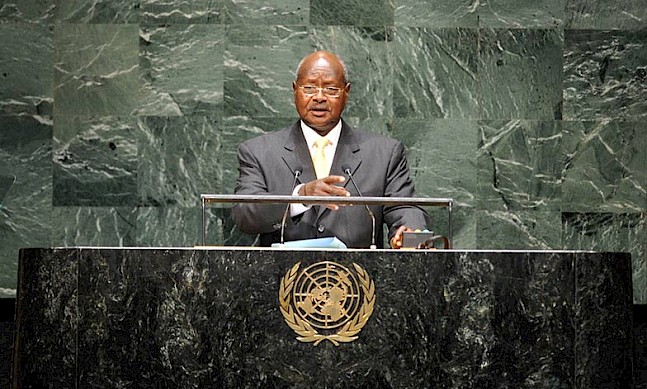

TRC: What has been your experience so far in partnering with the Ugandan government?

BK: This project had a long, and difficult, history before we got involved. I think a lot of mistakes were made previously, but the government worked very closely with the World Bank, with the IFC and sponsors like us, to put together a process that was credible, regimented, had milestones and was something that you could look at and see a clear way forward. The government and all the stakeholders really did a lot of good work upfront to create that atmosphere.

TRC: What is being done to minimize the environmental impact of the project?

BK: We have put a tremendous amount of effort into that. The environmental impact study for us in a hydro project is probably one of the most challenging and risky components.

We spent millions of dollars and a lot of hours focusing on making sure all affected people are at least as well off as they were before we arrived. We had to make sure of free, prior informed consent, which sounds like a simple thing to do but you have to go about it very carefully, especially when you have cultural or communication differences to ensure that people really understand. We also spent $14 million on projects that we think will help improve the situation for the affected people, whether those are schools, health clinics, job training, access to electricity, access to water supply and things of that nature.

It takes a lot of census and data collection to be able to put together these programs in a way in which they really have a positive impact. On the environmental side, Bujagali had no species that were significantly adversely affected. Other projects are now using our study as a template because it’s a world-class approach. The key is to have a balance between development benefits and environmental changes.

TRC: How does Uganda compare to other countries as an investment destination?

BK: When considering a project, you have an open and transparent process. Further, you need to be comfortable that you can develop and operate the business in an open way. We’ll never touch a country where corruption is the way things are done. That was a huge draw to Uganda for us in that we could see that we could do the entire project in an entirely clean way. Secondly, I’d say that the rule of law and the consistent application of law is a hugely important issue for us, and again Uganda passed that mark as well. And there’s the need for broad and strong support for the project from the government, which we fortunately had in Bujagali.

TRC: What would be your message to investors considering Uganda?

BK: We think that sub-Saharan Africa, and Uganda in particular, is a really exciting place to do business. There are very few parts of the world where you can make investments that you are proud of socially and that are also good business deals.

In the first year of Bujagali’s operations, GDP growth increased by 76 percent. That’s just an amazing thing to be part of. I really see the improvement in the lives of people and it’s rewarding as an investor to be able to do that. Sub-Saharan Africa is a different challenge than a lot of other places that we invest in, and the key is in picking the right country and the right model. You have to have the right structure where the project benefits from the best attributes of both the private and public sectors. Blackstone has committed to invest $5 billion on energy projects in sub-Saharan Africa and that alone speaks louder than anything else as to their intentions and how they see the promise of the region.