As the curtain opens on a new era of peace, the Basque Country is determined to keep industrialising its resilient economy and reinforce its status as a hotbed of innovation, education and culture.

It may be a small region of only two million inhabitants, but the Basque Country represents many different things to different people. Its rich rural life and wealth of traditions reflect its status as home to one of Europe’s oldest peoples, who speak the enigmatic Euskara language. Meanwhile, its factories and businesses are testament to its history as an industrial heartland. And yet, the extravagant design of the Guggenheim art museum in Bilbao offers yet another view: a region that cherishes culture and which is prepared to launch itself into the future.

Even pinning down the exact geography of the Basque Country can be difficult. Many of the region’s nationalists regard the territory of Navarre and the three Basque provinces in south-western France all as part of what they call Euskal Herria, or the Basque homeland. But only the three provinces in Spanish territory that sit between the Pyrenees and the Bay of Biscay – Alava, Biscay and Gipuzkoa – form the autonomous community of the Basque Country, the focus of this report.

The region has provided some of Spanish history’s most illustrious figures, such as circumnavigator Juan Sebastian Elcano, Jesuit founder Ignatius of Loyola and the philosopher Miguel de Unamuno. But down the centuries, the Basques have had a complex relationship with the rest of Spain. In medieval times they enjoyed special status, being allowed to uphold many of their ancient laws in return for respecting the sovereignty of the Spanish monarch. Centuries later, during the centralising dictatorship of Francisco Franco, Basque autonomy was reined in and its culture was repressed, a policy that would both provoke a resurgence of nationalist pride and have violent repercussions.

Photo: Basque government - Mikel Arrazola

Photo: Basque government - Mikel Arrazola

Unity in a diverse political spectrum

Nationalist Party (PNV), which dominated the region for three decades after the advent of democracy, is back in government again, the political landscape has opened up in recent years. In 2009, the Basque Socialists (PSE) formed a groundbreaking, three-year governing partnership with the conservative Popular Party (PP). Then in 2011, a new coalition of leftist parties, Bildu, ran the PNV a close second in regional elections, heralding the arrival of a powerful pro-independence movement.

Three years of peace

In the democratic era, the Basque region’s autonomy has been restored, although not as much as many – both moderates and extremists – would like. From the late 1960s, the separatist group Eta waged a terrorist campaign for an independent state, killing over 800 people and deeply dividing Basque society. Police action and legal pressures would help weaken Eta until it declared a definitive ceasefire in October 2011, a move former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan described as “a victory for dialogue and peace”. Three years on from that landmark development, the region has adjusted to a new climate of peace which has benefitted not only ordinary Basques, but also tourism and other industries.

“This time of peace has to be an opportunity for the development of the Basque economy,” says Inigo Urkullu, the Basque regional premier, or lehendakari, of the moderate Basque Nationalist Party (PNV). “If we were able to grow during a time of violence, now we must be able to grow even more, especially once we get over the economic crisis.”

That crisis has hit Basques less hard than the rest of Spain. With an unemployment rate that is well below the national average – and around half that of Andalusia – and an industrial sector which in many cases has successfully reached abroad during Spain’s downturn, Urkullu’s optimism seems justified.

The region has long been famous for its ability to innovate and this trait can be seen in the business sphere. Many smaller Basque firms have pooled their resources by forming cooperatives and taking part in clusters. The region is also home to corporate giants, such as BBVA in banking, Iberdrola in energy and SENER in engineering and construction, all of which have relied heavily on new ideas to develop their business.

“This time of peace has to be an economic opportuniy”

Inigo Urkullu President of the Basque Country

Post ThisA creative brand

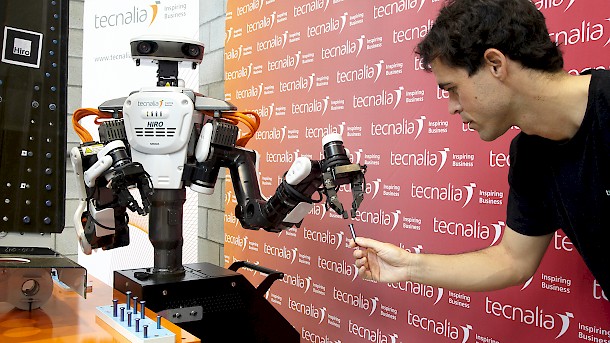

This creativity makes the Basque Country “a living lab of innovation and strategy development,” according to Joseba Jauregizar, who as managing director of Tecnalia, an alliance of technology firms, is at the heart of the Basque Country’s efforts to expand its industry. Once one of the world’s biggest iron ore producers, the region is now renowned for its diversification into areas such as renewable energy, nanotechnology and biotechnology and industry currently represents a quarter of its GDP.

The Basque pioneering spirit is not confined to business. It can be seen in the earthy sculptures of Eduardo Chillida, the eerie “painted forest” of artist Agustin Ibarrola, the experimental novels of Bernardo Atxaga and, perhaps most famously, in the envelope-pushing dishes of its chefs, who have taken global haute cuisine by storm. Such cultural energy, allied to the region’s business character, made the creation last year of a “Basque Country brand” a logical step, even though it ruffled the feathers of those in Madrid who are leading the equivalent “Spanish brand”.

Given its impressive record on employment, technology and education, the Basque Country can approach the social, economic and environmental targets the EU has set out for its members in the Europe 2020 strategy with confidence. Another challenge for the region is to consolidate the peace that arrived in 2011 and leave the trauma of the Spanish economic crisis behind. “The Basque tradition is that desire to offer an excellent product and this is something that goes right back to the traditional small businesses here – the local workshop,” says Jose Manuel Orcasitas, CEO of coach manufacturer Irizar. “Now, in modern times, the region’s big focus is on innovation, so providing a high-quality result is what it is all about.”

Fast Facts

Researchers working on Basque industrial policy in the public and private sector

People employed in the life sciences sector

Strategic industrial clusters have been set up in the Basque Country

The Basque people

Photo: Basque Tourism Agency

Photo: Basque Tourism Agency

The history of the Basque people has been the subject of many, later discredited, theories down the centuries, including the notion that the Basque people are descended from Turks or Magyars, or that the Basque language, Euskara, was once spoken across Europe. One more outlandish theory is that Noah was Basque. The roots of the Basque people remain shrouded in mystery, and as anthropologist Joseba Zulaika wrote, “Basque identity is founded on an acute sense of their enigmatic past.”

Euskara, however, has provided some clues to Basque history. Its utter distinction from other Indo-European tongues reinforces the idea that the Basques who settled in the north of the Iberian Peninsula were among the first inhabitants of western Europe.

The territory known as Vasconia, a precursor to the present-day Basque Country, existed in the middle ages in the western Pyrenees, although it would be fragmented and re-shaped down the centuries due to pressures from France, Castile and Aragon. In the late 19th century, a young Biscayan called Sabino Arana became the driving force behind modern Basque nationalism, helping standardise the Euskara language and bolstering the notion that the region’s people were of a separate race from the French and Spanish. However, Arana’s more extreme ideas have since been disregarded, especially as the arrival of immigrants has significantly altered the Basque region’s ethnic make-up. Many of today’s inhabitants of the Basque Country come from North Africa, South America and Eastern Europe.

One thing has not changed over the centuries: Basques are known for being industrious, reliable and honourable. The Spanish saying “palabra de vasco”, or “word of a Basque”, is still used to describe the solemnity of a promise.

Tecnalia´s Hiro robot demonstrates its capabilities at the BIEMH. Photo: Tecnalia

Tecnalia´s Hiro robot demonstrates its capabilities at the BIEMH. Photo: Tecnalia

Innovation

Robust investment in research and development has become crucial to the region’s quest to compete. At just over two percent of GDP, Basque investment in this area is well above that of Spain as a whole and higher than the EU average. Education is a key part of that strategy, with 43 percent of young Basques holding university qualifications. “We have had to be very competitive in order to survive,” points out the regional premier, Inigo Urkullu. While the backing of different regional governments for research centres and new technology projects has been fundamental in the innovation drive, so too has the involvement of the private sector. Perhaps the most visible example of Basques’ willingness to embrace innovation is Bilbao’s Guggenheim art museum, whose design, by Canadian-born architect Frank Gehry, has not only awed visitors but also helped transform the city.

Photo: Basque Tourism Agency

Photo: Basque Tourism Agency