Despite its status as the cradle of Basque identity, this north-eastern province has a modern outlook on business, while its political leaders are pursuing innovative ways of governing.

Tucked between the south-western corner of France and the Bay of Biscay, Gipuzkoa may be a small province but it is one of many parts. The lush landscape of rolling mountains to the south gives way to a coastline to the north that includes sleepy towns and the buzzing cultural hub of San Sebastian. The province is the heartland of Basque nationalism, and today it has the highest proportion of speakers of the Basque language, Euskara, of the three Basque provinces in Spain.

It has also created a strong economic identity. While Biscay has traditionally relied on large-scale business, Gipuzkoa has built its economy on small- and medium-sized companies, with 80 percent of its firms employing fewer than ten workers.

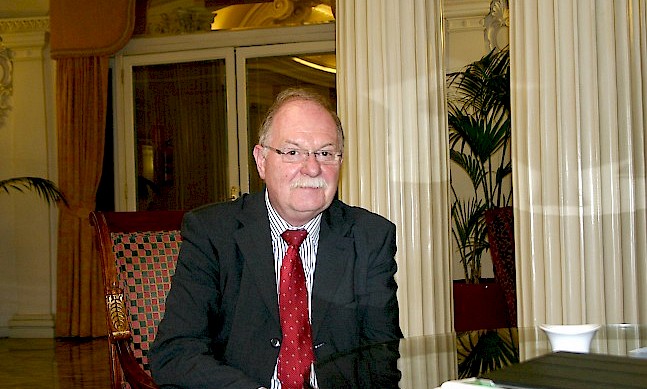

“We’re all Basques, but we’re different,” explains Martin Garitano, president of the provincial council of Gipuzkoa. “Biscay has its own character, while the Gipuzkoan is more reserved – we’re talking about small, self-made business owners who came from a rural background and who have developed industrial careers.”

As well as having a reputation for being less extrovert than their neighbours, Gipuzkoans are known for their reliability and determination. This region, like Alava and Biscay, has invested heavily in research and development in recent decades, spending just over two percent of GDP on this sector – nearly double the Spanish average.

The three provinces that make up the Basque Country each have their own, unique identity

The three provinces that make up the Basque Country each have their own, unique identity

Stability through unity

This entrepreneurial drive contributed enormously to the Basque region’s economic expansion during the 20th century, when it established itself as one of Spain’s main industrial motors. Although the famously robust Basque economy could not avoid the economic crisis which has swept over Spain over the last five years, it has sidestepped the worst of it. Gipuzkoa’s jobless rate of around 14 percent is the lowest in the country. “Why do we have lower unemployment?” asks Pedro Esnaola, chairman of the Gipuzkoa Chamber of Commerce. “Our market is in just as bad a condition as any other. But entrepreneurs have decided to keep jobs, in many cases by becoming personally indebted in order to keep the business going.”

That determination to prioritise jobs can also be seen in the cooperative culture, which has thrived in Gipuzkoa, most famously at the Mondragon group (see inset). Set up nearly 50 years ago as a pioneering corporate scheme, it now includes around 290 companies around the world. While the group has gone through financial difficulties recently, it prides itself on having managed, throughout its history, to save jobs through its labour redistribution formula.

“The main goal of a cooperative model is not profitability, although obviously you also need that, or else you will be forced to shut down,” says Jose Luis Perez, who is chairman of Orkli, a cooperative within the Mondragon group. “The main thing is to keep jobs here, and you do that by reinvesting.”

Although Fagor, the Mondragon group’s flagship firm and one of Europe’s largest consumer appliance companies, was forced into bankruptcy in 2013, advocates of the cooperative model believe it is here to stay. “We are a very collectivist society,” says Jon Altuna, vice-rector of Mondragon University, which is closely associated with the group. “Just look at the gastronomic societies we have.” Mondragon alone has 30 of these dining clubs, which regularly bring together friends, relatives and colleagues to cook and eat, reflecting the tight-knit nature of Gipuzkoa’s social and business life.

This cooperative ethos has also helped companies secure financing when credit has been tight in recent years. Firms collectively approached the government to ask it to guarantee their financing through so-called SGRs, or reciprocal guarantee companies. “We were able to solve the problem through cooperation, while retaining our individual corporate independence,” Esnaola says.

“We have been silent for a long time, partly due to our recent history”

Maria Lasa Irizar Managing director of Irizar Forge

Post ThisCasting off the Gipuzkoan reserve

Since 2011, businesses have been free of a very different burden, following the announcement by terrorist group Eta of a definitive ceasefire. This was a particular relief for this province, which had been a focus of much of its violence. However, one concern that does remain within the business community is that the famous Gipuzkoan reserve has held back the province’s ability to sell itself and its products within the global economy.

Orkestra-Basque Institute of Competitiveness, a centre for the analysis of Basque industrial policy and strategy that partners with Deusto University, has drawn up a roster of what it calls “hidden champions” – successful yet relatively unknown companies. Irizar Forge, which manufactures hooks for winches and cranes, was included as one such case.

“We have been silent for a long time, partly due to our nature and partly due to our recent history of terrorism,” says the company’s managing director, Maria Lasa Irizar, speaking of the business sector as a whole. “However, I think that we need to acknowledge that times have changed and start doing more to ensure that people on the outside know about all the good things that we are doing. I think we need to sell ourselves a little better and believe in ourselves.”

Entrepreneur viewpoints

“There are lots of clichés about the Basques, but clichés tend to exist for a reason,” says Joseba Egana, CEO of Kendu, a Gipuzkoa-based firm which specialises in visual communication. “I think what we can do is represent good things like hard work, responsibility and reliability, things which Spain is perhaps not internationally famous for.” Jose Luis Perez Garmendia of manufacturing firm Orkli says “reliability, technology, innovation and customer service” are all typical of the province and the wider region. “When you have a lot of businesses acting in this way, it conveys an image.”

The provincial council building in Gipuzcoa. Photo: Basque Tourism Agency

The provincial council building in Gipuzcoa. Photo: Basque Tourism Agency

New policies and new politics

The Basque region has seen a seismic political change in recent years with the arrival of Bildu, a new, leftist, nationalist coalition. In 2011, it came a close second to the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) in regional elections and swept to power in many town halls, particularly in Gipuzkoa.

In contrast to the Spanish central government, Bildu’s leftist ideology has seen it battle the tail-end of the economic crisis with relatively heavy investment in the business sector, social spending and culture. San Sebastian, which Bildu governs, raised investment in entrepreneurial projects from €1 million to €7.5 million between 2011 and this year. Unusually, the city has also become involved in investment policies related to the labour market, which would normally be under the control of regional and central administrations. San Sebastian city hall has apportioned €20 million over three years to job creation projects.

For Juan Karlos Izagirre, mayor of San Sebastian, this is all part of Bildu’s efforts to bring politics closer to the Basque people.

“We are trying to implement a bigger policy at a social level against the economic crisis than anyone else has done, either here in the Spanish state or in many other European cities,” he says.

The cooperative model in practice

As a Mondragon company, DanobatGroup's employees are part owners of the company. Photo: DanobatGroup

As a Mondragon company, DanobatGroup's employees are part owners of the company. Photo: DanobatGroup

Mondragon Group

A Biscayan priest who was driven by the importance of education and democratic ideals is seen as the driving force behind the creation of the Mondragon group. In 1956, Father Jose Maria Arizmendiarrieta blessed the creation of a company, Ulgor, which was based on the cooperative ethos. This company would later become white goods firm Fagor. He also upgraded the Escuela Profesional, a vocational training school, and by 1959, credit provider Caja Laboral Popular had been created, also on the basis that its staff were part-owners of the business. As the Mondragon group’s companies expanded their activities abroad, cooperatives in other areas were set up and an autonomous welfare system offering workers healthcare and job protection was developed. At the end of 2012, the Mondragon group was employing 80,000 people in finance, retail, industry and knowledge.