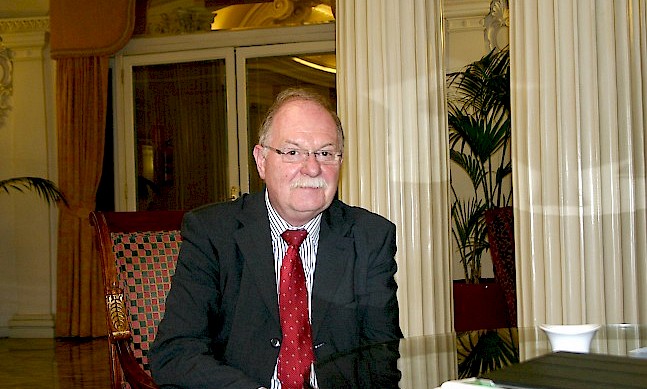

Photo: Office of the Mayor of Bilbao

Photo: Office of the Mayor of Bilbao

An architect by trade, Bilbao’s mayor Ibon Areso played an important role in his city’s extraordinary regeneration programme before joining politics. He met with The Report Company to talk about his plans for the future, and explain how the city was transformed.

The Report Company: How did you become involved in Bilbao’s transformation?

Ibon Areso: Before I was elected to Bilbao’s council, I was under contract to it as director of the office charged with making the new plan for the city. I am an architect and urban planner and one of those fortunate people to find a job doing what they studied for. The city had to change, it was foundering. We had an economic model of heavy industry – steel, ship building, mechanised fishing and equipment manufacture – that collapsed and left us with unemployment at 25 percent in the metropolitan area. We had to do something about that situation.

TRC: What were the main milestones that led to the city's rebirth?

IA: Our main goal was regeneration. What worried us at that time was employment, which was no longer going to be in industry as it had been for the previous 200 years. We needed to move to a services economy. The services sector needs far more carefully looked-after and selective surroundings than an industrial city, so we needed to change our physical appearance.

The strategy was based on a series of concepts that can be divided into four pillars. The first two are physical, and more urban, and the second two are more socio-economic in nature. We called the first plan interior city mobility and making the city accessible to the outside world. This means the port, airport, road and railway upgrades, the underground and so on. We needed good infrastructure without forgetting intelligent communications such as fibre optic and broadband.

The second pillar was to improve the environment and the appearance of the city; improve air quality, clean up the rivers and industrial areas, change the city with more parks and walkways. We just wanted to make the city a more agreeable place to be.

The third pillar was investing in human resources and technological transformation.

Nowadays, the cities that are better off are not those that have more natural resources, they're the ones with better-trained people. The world we live in and the world of the future are all about knowledge.

The fourth pillar was cultural activity. We know that cultural, artistic, and free time activities are not only important for the city's inhabitants, but are also one of the best ways of helping to project the city's image abroad. Culture is a good way of publicising cities. One of these elements would be the Guggenheim museum.

“Normally administrations put culture in the expenses pile. But culture isn't an expense; it's an investment that generates wealth.”Tweet This

TRC: What does the Guggenheim mean to Bilbao?

IA: Having the museum here is a miracle for two reasons. Firstly, in 1991 when we found out that the Guggenheim Foundation wanted to open a site in Europe, and wanted to internationalise, we invited them to come here. You have to see how Bilbao was before; it was a disaster. They were shocked. Why did they come here then? We had already set out a plan of what we wanted to change, but that didn't influence their decision. They came because all the other cities they visited had turned them down. The only firm offer they had was from us. So they either had to get in bed with the devil or go home empty handed to New York.

You must remember that at that time, everybody was against it. Everybody thought that all available public resources should be put to helping industry and reducing unemployment, not to build a contemporary art museum which people thought was completely frivolous. We had to open the museum with 95 percent of people against us. Our conviction was a change in mindset. Normally administrations put culture in the expenses pile. But culture isn't an expense; it's an investment that generates wealth, and we were able to make people see that. It was risky, but it paid off.

TRC: Now that Bilbao has been transformed into a modern city, is the process complete?

IA: No. We’ve received over 30 regeneration awards, but in an ever changing world, if we rested on our laurels, we would end up getting left behind in no time at all. Our first plan was to change the city from an industrial one to an agreeable place to be. The second part of the plan is to move the city from being agreeable to being intelligent, a city of knowledge. The intelligent city is one whose economy takes its surroundings into account. We are a medium-sized European city, but business on a certain scale needs more critical mass. Therefore we have to create synergies with councils around us so we can increase our size and make more advanced services available to the creative industries.

TRC: What surprised you most about Bilbao’s regeneration?

IA: What you can never know is how far you're going to be able to take the reality of city planning. We have really achieved great things though. We owe a lot to the Guggenheim museum because it placed us on the world map even though we're a small to medium city. The danger with that though, is that it takes the attention away from other areas. The process of change is a lot more complicated. The investment in the Guggenheim is nothing compared to the investment in the whole process and needs strategic reflection.

Focusing on the museum gave rise to a surprise effect that we call the "Guggenheim effect."

“We have to create synergies with councils around us so we can increase our size and make more advanced services available to the creative industries.”Tweet This

The museum cost €133 million euros. €85 million of that went to the building, plus the land provided by the council. Fifty percent of the project was financed by the Basque Government and the Biscay provincial council.

To get that investment, an economic viability study was carried out and we were told the museum would have to have 450,000 visitors a year for it to be profitable. We didn't know if we could reach that figure. Our reference was the Museum of Fine Art that had around 70,000 visitors, so that figure of 450,000 seemed out of reach for a new museum. We forged ahead however, and the bet paid off far better than we could have hoped. In its first year of opening, the museum received 1,350,000 visitors, three times the amount we thought we would get. And even now the novelty has worn off, visitor numbers are still around 1,000,000 a year. The GDP of the Basque Autonomous Community generated solely from building the museum was €144 million in the first year of operation.

Society paid for the museum in less than a year. That wealth, now about €200 million per year, generated taxes. Society got its money back from the museum in less than one year, and the council in less than five. The administration worked out the increase in tax revenue generated by the museum. The museum employs around 4,000 people. Economically speaking, that's the "Guggenheim effect". Another element is that we were a society that always received a lot of negative press from abroad. If we had to put a value on the amount of positive press around the museum, it would have cost us more than €133 million if we had to pay for it.

It moved Bilbao's image away from bombs and terrorism; if the Guggenheim museum came here, so can you. The third, more intangible element is that Bilbao society was completely derailed by the crisis and had no faith in the future. The museum's success started to improve its self-esteem. For a society to move forward, it has to believe in itself. Bilbao’s people have always had a very entrepreneurial spirit and we were able to move forward because of that spirit.

TRC: What does innovation mean for Bilbao’s council?

IA: Innovation is fundamental. We can't compete on the salaries we offer in the short term.

We can only compete with innovation and knowledge; not in classical manufacturing, where Europe has traditionally been the main world supplier. That's why innovation is a key challenge.

“Innovation is fundamental. We can't compete on the salaries we offer in the short term. We can only compete with innovation and knowledge.”Tweet This

TRC: What is your approach to boosting what Bilbao has to offer in terms of education?

IA: We are focusing most on the university. Bilbao is not really known for being a university town and we want that to change. In the past the university was based on the outskirts of the city, but now we are building new spaces for a legal-economics campus, and so the school of engineering, among other projects, can have a technology campus. We are also developing a scheme whereby the university creates business incubators linked to the private sector to set up entrepreneurial programmes and implement them in the city's neighbourhoods.

TRC: How would you define your relationship with the UK?

IA: Just as San Sebastian has always had very close links with France, Bilbao has always been closely linked to the UK due to a long and continuing trading relationship. We exported minerals and iron, and when the first foundries were set up here we imported coal.

We do a lot of business with the British Chamber of Commerce, and London is a financial centre for many things that are important to us. We have also got contacts for entrepreneurship and technology and we want to start to do exchanges and take advantage of opportunities in England.

TRC: What would you like people to know about Bilbao?

IA: Bilbao is a lovely city to visit and I would like to invite people to come here.

The Financial Times called Bilbao the third most attractive city in southern Europe for investment, and the city with the best economic prospects. That’s just something to remember. I invite people to come here and enjoy the city, but also to invest and take advantage of the opportunities we have here.